The public’s first look at Nike’s Alphafly wasn’t pretty. In August 2018, the anonymous Instagram account @protosofthegram posted a blurry, cropped photo of disembodied ankles sprouting from a nondescript black upper attached to a chunky slab of what looked like the Vaporfly’s ZoomX foam. The caption stated that an air unit was hidden in the forefoot and that the legs belonged to Eliud Kipchoge. This was the first hint of how Nike planned to follow up on its record-breaking Vaporfly, though Kipchoge had already been testing prototypes since January.

In the two years leading up to that point, Nike’s new Vaporfly, then unique for its thick, bouncy Pebax foam midsole and carbon-fibre plate, had upended the less-is-more maxim governing racing flats by winning – sometimes sweeping – nearly every major marathon it entered. And in the month after those first mysterious photos, Kipchoge, wearing Vaporflys, would claim his first marathon world record in 2:01:39 at the 2018 Berlin Marathon.

More photos of the new prototype, midsole seemingly (and bewilderingly) thicker than the Vaporfly’s, surfaced every few months until, in October 2019, in Vienna, Kipchoge wore a polished version of the still-unnamed shoe to clock the first sub-two-hour marathon in recorded history at the Ineos 1:59 Challenge. The following June, the Air Zoom Alphafly Next% was released and, last year, was updated as the Alphafly 2. Meanwhile, Kipchoge has worn Alphaflys to lower his official world record to 2:01:09 and claim his second Olympic marathon gold medal.

While the new shoe, with its added air chambers, is an obvious evolution from the Vaporfly, the Alphafly is mechanically familiar: a generous block of responsive foam stabilised by a heel-to-toe carbon-fibre plate. That’s no longer a mystery. But how, exactly, does that system translate physiologically to the fastest marathon(s) ever run? That’s what biomechanists are still trying to work out.

Thinking big

The premise of the Alphafly is simple, says Carrie Dimoff, the Nike director of innovation who leads the Alphafly development team. ‘If we can store more of your energy, we can return more of that energy and you can run more efficiently.’

All of running is energy maintenance, from our shoes to our stride. ‘We’re essentially giant springs as we run,’ says Geoffrey Burns, a sports physiologist at the US Olympic Training Center. In the air, between footfalls, we’re gathering potential energy both from the forward motion of our previous step and as gravity pulls us down. When our feet strike the ground, our bodies begin accepting and storing that now-realised potential energy, mostly in our muscles and tendons. Then, in dynamic concert, these muscles and tendons recycle that energy, adding a bit of effort to maintain our kinetic momentum, and push us forwards off the ground and back into the air. Researchers quantify how much energy we each require to run – our ‘running economy’ – by measuring the amount of oxygen our muscles demand during an effort we can sustain for hours.

In 2017, researchers from the University of Colorado and Nike published a study in the journal Sports Medicine showing that runners averaged a 4% improvement in running economy wearing a Vaporfly prototype compared with when they wore Nike’s racing flat, the Zoom Streak 6, or the 2016 Boston Marathon-winning Adidas Adizero Adios Boost 2, also a flat. Months later, Nike tied its shoes to this improved running economy when it launched the Zoom Vaporfly 4%.

The highly cushioned Vaporfly was a paradigm shift, sending shoe developers, footwear researchers and runners on a quest for shoes promising biomechanical efficiency. ‘We’d been saying forever that minimal was better,’ says Dimoff. ‘We needed these specific study numbers to explain why people should trust, suddenly, this very tall shoe.’

The idea that a shoe with those attributes could be fast had been a revelation at Nike, too, and in June 2016, almost a year prior to Kipchoge’s first sub-two marathon attempt wearing Vaporflys, a development team was already working to see how far they could push this cushioned propulsion. ‘We weren’t looking to invent a companion shoe to the Vaporfly,’ Dimoff says. Instead, they were asking how they could make the system more energy efficient.

'We started thinking about the Nike Zoom Air technology,’ says Dimoff, referencing Nike’s trademark air-filled rubber cushioning, which debuted in the Air Tailwind running shoe at the 1978 Honolulu Marathon. As a component, they knew these air pods could return more energy to the runner than Nike’s springiest foam. ‘Our hypothesis was that we could make the system more efficient by swapping some of the foam for air,’ says Dimoff.

To find out, Nike researchers conducted mechanical tests on individual components – air units, foam, plates – to answer some initial questions: how much energy was stored? What shape is the deformation curve? Which returns the most energy?

They designed and built the air units first, then began cobbling together prototypes around them. Systems of components came next, with partial builds put through further mechanical testing. By late 2016, wear-testers were already putting the first of hundreds of prototypes through their paces on treadmills and across Nike’s campus. Throughout the process, Dimoff says, they were looking for ‘the right balance between what the science told us was performing the best and what the runners told us was the most comfortable; the ones they had the most confidence in’.

Finally, in January 2018, Dimoff and team took the first of at least five rounds of prototypes for Kipchoge to test at his training camp in Kaptagat. ‘We think we have something even better,’ the design team had told him. Kipchoge was game to try it. ‘He just put them straight on and ran,’ says Dimoff. ‘There was no hesitation. He just saw innovation.’

Foam truths

The heart of the Alphafly – and its Vaporfly cousins – is not the much-discussed carbon plate, but the ZoomX foam. ZoomX is Nike’s custom formulation of Pebax, a proprietary polyether block amide (PEBA) thermoplastic elastomer (flexible plastic). A PEBA’s chemical structure can be precisely ordered to exhibit a staggering range of properties: hard enough to form the top layer on skis, soft enough to be worn as a waterproof jacket, or, as with ZoomX, puffed into a foam. Nike has been deploying it as the hard outsole on the bottom of its cleats since the 1990s and, beginning in 2000, as a foam plate, in the Shox R4 running shoe.

This capacity for precision tuning is also what allows PEBA foams to be made softer or firmer, bouncier or more rigid, depending on the goals of the application. Nike declined to discuss the details of the development of its Pebax foam, but did say it manufactures ZoomX to produce different benefits for different shoe models. ‘In the Alphafly and Vaporfly, we’re manufacturing [ZoomX] to produce the most energy return,’ says Nike Running footwear product manager Elliot Heath. ‘Whereas, in the Invincible [trainer], we’re manufacturing the same material a little differently to produce cushion for everyday runs.’

Critically, for the Alphafly and Vaporfly, PEBA could be optimised to produce a foam with properties previously thought contradictory: tall but lightweight, plush but springy. In a shoe midsole, all foam – like our legs – acts as a spring: it absorbs and stores potential energy when compressed by the foot (known as compliance) and returns a portion of that energy as the foot rolls on to its toes and pushes off, when the foam rebounds to its original shape (known as resilience).

Midsole foams – EVA, TPU and PEBA – vary in their capacity for compliance and resilience. And none give back as much energy as they get. At its best, the standard EVA foam used in most shoes returns around 65% of the energy put into it, Burns says. The Adidas Boost 2’s fairly unique TPU foam, measured in the original Vaporfly 4% study, returns a laudable 76%. And in that same study, the Vaporfly’s ZoomX foam was found to return an unprecedented 87%. ‘Everyone at the time made a huge deal about this carbon-fibre plate, but that foam is the magic, that’s the game changer,’ Burns says.

But the amount of energy midsole foams return is only half the equation, Burns says. It depends on how much is stored. Consider the thin rubber soles on minimalist shoes, he says. They return nearly all the energy put into them. But because they’re not compliant and can hardly be compressed, they store virtually no energy and return little to a runner.

Likewise, the energy returned by the three foams in the Vaporfly 4% study – 65%, 76% and 87% – was a percentage of the total energy those foams were able to store to begin with. And when the researchers measured this storage capacity, they found the Vaporfly prototype’s ZoomX, when compressed, stored nearly twice the energy of the other shoes. When this superior energy storage capacity was compounded by the foam’s superior energy return, overall, the Vaporflys returned more than twice the amount of energy per step. The authors credit ‘its substantially greater compliance rather than the greater percent resilience’.

The foam’s weight, or lack thereof, is what makes all this possible. ‘For a very resilient spring, the longer it is – the stack height of a shoe – the more energy you can store,’ says Burns. But increasing the stack comes with a weight penalty. Studies have quantified this ‘cost of cushioning’. In a pair, every 100g of added weight per shoe reduces running economy by roughly 1%. The Adidas Boost 2’s TPU improved on traditional EVA, but that racing flat weighs the same as the Alphafly 2, which stacks its lightweight ZoomX foam twice as high. ‘So,’ says Burns, ‘a super shoe is not just a high-energy return foam, it’s not just a compliant foam, it’s not just a lightweight foam. A super shoe needs all three of those things.’

But what about that carbon-fibre plate? When the Vaporfly debuted, despite the bouncy, lightweight foam, the running world seized on the plate and armchair biomechanists labelled it a spring that propelled the runner forwards (akin to the carbon-fibre blades used by some Paralympic sprinters).

Cries of technological doping rang out – at least until Nike’s competition produced their own super shoes. A 2022 study in which Wouter Hoogkamer, who led the original Vaporfly study and now conducts research at the University of Massachusetts Integrative Locomotion Lab, took a saw to the forefoot of a pair of Vaporflys, making six lateral cuts through the bottom of the shoe and the plate, and then compared subjects’ performance in them versus wearing an intact Vaporfly. While the study only tracked 13 participants, the sliced plates worsened subjects’ running economy by only 0.5%. And, lining up with previous studies on carbon-fibre plates, the intact Vaporflys produced longer ground contact time and a noticeable forward shift in ground reaction forces, suggesting the plate, instead of acting as a spring, is guiding forces into the forefoot, acting like a stiff lever, and increasing the stance’s propelling phase.

This fits with Dimoff’s description of the plate’s purpose. ‘It stiffens the shoe to reduce joint work and allow your stride to be more efficient,’ she says. Highly pliant cushioning inherently lacks not only stability, but also coordinated forces. The plate brings the centre of pressure to where we need it under the foot, says Iain Hunter, an exercise science professor specialising in running biomechanics at Brigham Young University, US, who, in 2019, published a study in the Journal Of Sports Sciences independently validating the findings in the original Vaporfly study. During our footstrike, ‘the force under the foot drifts forwards, builds and peaks around the middle of the time we’re on the ground’, he says. The foam compresses, storing energy, and then the plate, because of its rigidity, positions the foam to,‘give that energy back close to the time the person needs it’. Imagine a tall, plate-less midsole made of marshmallow. Without the guidance of an internal structure, the edges would cave, the energy would disperse.

The plate’s sculpted shape, with a spoon-like dip in the forefoot, makes this choreography possible. ‘We want your foot to roll efficiently,’ says Dimoff. ‘A flat plate would be a slappy experience. That would actually add work.’

The Alphafly uses the same plate, though its shape has been tweaked to distribute force across the dual Zoom Air chambers. ‘When you put your force into the shoe, whether you’re striking medially or laterally, the air’s not shooting off to the other side and creating a tipping point,’ says Dimoff. Tensile nylon fibres aid in channelling your energy back, tethering the bottom of each chamber to its top, creating a flat floor and ceiling, a puck-like shape that loads and returns forces vertically. The energy return of the chambers tests upwards of 90%, Dimoff says.

In summer 2021, Dimoff’s team began Alphafly 2 prototyping with a new goal: improve the shoe while making its advantages accessible to more runners, those training to break three, four and five hours in the marathon. Wear-testing was expanded to more types of runners and the Alphafly 2’s base was widened by a centimetre, the air chambers now sit on a sliver of foam, the heel drop was bumped from 4mm to8mm and padding was added to wrap the heel and top of thef oot in a closer, softer hug – an overall tune-up that increases lateral stability and smooths the transition into the forefoot.

The shoe’s foam, plate and air units remain the same, running just as efficiently as the generation before it. Not that anyone but Nike knows exactly how or why any Alphfly always tests out on top.

Secret source

The Alphafly's eminence is, theoretically, easy to explain: it’s simply a better spring. But the world’s top running biomechanists and kinesiologists have taken the shoe, or the Vaporfly, into a lab to define why they’re superior to the super shoe competition that’s emerged, and the results are inconclusive. They’ve essentially admitted as much. ‘Th e better running economy... cannot be currently explained from a biomechanical standpoint,’ a group of researchers from the University of Lausanne Institute of Sport Sciences and the Volodalen Swiss SportLab wrote in a 2022 Footwear Science paper. In the same issue, Benno Nigg, founder of the Human Performance Lab at the University of Calgary, Canada, and textbook-writing titan of the biomechanics field, notes Nike’s foam-and-plate story, but concludes, ‘They do not (publicly) provide a functional explanation of the mechanism by which these features could improve running performance.’

There are various theories, all backed by some evidence, on how these shoes improve running economy. None of it is conclusive, though some is converging. In both the original Vaporfly study and Professor Hunter’s follow-up, subjects wearing Vaporflys showed slightly longer stride lengths. Professor Hunter’s study also found those wearing Vaporflys ran with greater vertical oscillation, more bounce in their step, while Hoogkamer’s study found they ran with greater ground reaction force. Are faster or heavier runners loading the foam with more energy and getting more returned? Maybe the tall, lightweight midsole is extending the length of the leg with a non-fatiguing material? Hoogkamer’s study showed heel strikers saws lightly greater improvement in running economy than midfoot strikers. Are they utilising more of the foam? Several studies adding carbon-fibre plates to traditional midsole foams have shown the same benefits for heel strikers.Maybe these runners are simply leveraging the full potential of the plate?

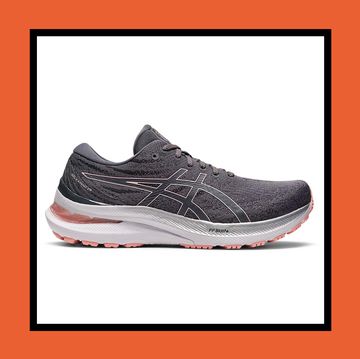

Another 2022 Footwear Science study, by Dustin Joubert, professor of kinesiology at St Edward’s University in Austin, Texas, presented results from head-to-head research that measured the Alphafly against other current super shoes (the Hoka Rocket X, Saucony Endorphin Pro, Asics Metaspeed Sky, New Balance RC Elite, Brooks Hyperion Elite 2, and the Vaporfly Next% 2). On average, the 12 subjects showed the greatest running economy in the Alphafly, though the Vaporfly was a close second. But Professor Joubert doesn’t know exactly why.

He found correlations hinting at how the shoes are working and who is benefitting, though with only 12 participants, none of the explanations ‘popped out’ as much as he would have liked. In agreement with Hoogkamer and Professor Hunter, Professor Joubert’s study found the Alphaflys produced the longest stride length, and the shoe’s lowest responders, those who saw the smallest gains in running economy, ran with lower vertical oscillation than the other runners. And the subject with the lowest vertical oscillation was the only complete non-responder to the Alphafly.

In a follow-up study, published this year in the International Journal Of Sports Physiology And Performance, Professor Joubert, with Burns, measured the running economy gains in subjects wearing Vaporflys while running 8:00 and 9:30-minute/mile pace, in contrast with the 6:00 to 7:00-minute/mile paces typically employed in these studies. The results showed the Vaporflys, at slower speeds, still improved running economy relative to a traditional shoe, but less so, with subjects averaging a 1.4% improvement and 0.9% improvement, respectively.

Observationally, to Professor Joubert, the studies converge. In Alphaflys and Vaporflys, larger ground reaction force – stronger, faster, bouncier running – seems to generate greater improvements in running economy. ‘You can only get back what you put in,’ says Professor Joubert. He thinks a runner’s weight, too, could factor, especially in the bulkier Alphafly. ‘If you’re really lightweight and barely getting off the ground, how are you benefitting from these 40mm of cushy, stacked foam?’

The hypothesis gaining the most traction comes from Nike researchers’ 2019 Footwear Science abstract, showing that a group of Portland Marathon finishers wearing the Vaporfly 4% exhibited lower blood markers for post-race muscle damage. Anecdotal evidence for this is strong as well: running long in the Alphafly or Vaporfly, your legs seem to last longer, they’re not so taxed at the end and they’re less sore the next day. ‘Exercise physiology is coming to accept that muscle cramping late in the race has a lot more to do with muscle damage than hydration or electrolyte imbalances,’ says Professor Joubert. ‘From personal experience, the last marathon I ran, in the Alphafly, I was at mile 22 thinking, “What the hell is happening here? I’m not supposed to feel this good. When are things going to fall apart?”’

But Professor Joubert and others agree that none of this is evidence that the Alphafly is the superior shoe, or that any super shoe will be super for everyone. Across studies, at all speeds, individual responses to these shoes and their components ranges from 3% detriment in running economy to something like a 6% gain. ‘We each have a unique interaction with the ground,’ says Burns. And this extends to shoes, too. ‘The way you move through the footstrike and load that foam, and move over that plate, is going to differ for every single person.’ He sees the leading hypotheses proposing why the shoes are beneficial (the foam is returning more energy to the runner, the plate is guiding contact forces, etc) and why some runners benefit from improved running economy and others don’t (heel strikers or runners with higher ground reaction forces) – and he says they’re plausible. ‘But nothing clear yet.’

Next steps

It’s already happening again. This time, the first hints of the next Nike super shoe popped up at the December 2022 California International Marathon – six months after the Alphafly 2’s release – where a racer was seen wearing a prototype with a more angular chunk of white ZoomX under another plain black upper. At this January’s Houston Half Marathon, Conner Mantz was spotted in similar shoes en route to his sixth-place finish. Both pairs appeared to have white tape concealing the air units. And then at the Tokyo Marathon in March, a handful of elites appeared with a polished version, complete with the Swoosh and visible air pods.

Nike remains tight-lipped; spokesperson Erin Byrnes declined to even call it an Alphafly, referring to it instead as the company’s ‘latest marathon innovation’. But the familiar air units and similar foam contours are compelling evidence for a system update. Compared with the Alphafly 2, the prototypes appear to add a foam midfoot. This could, says Runner’s World US testing director Jeff Dengate, improve the shoe’s transition from heel to toe-off. ‘There’s also less rubber used in the back half of the shoe. Nike probably didn’t see much wear there, so the little patch there may save weight.’

Nike did share one detail, and perhaps it’s the only one that matters: the fastest marathon racer of all time is currently training in the shoes.

What are the Nike Air Zoom Alphafly Next% 2 like to run in?

The shoes that Eliud Kipchoge wore to break the sub-2 hour marathon have received a lot of attention since 2020 and the latest version, the Nike Alphafly NEXT% 2, is no different.

Launched in a 'Proto' colourway, the latest version has had a bit of an overhaul. It’s now an 8mm drop now from heel-to-toe (version one was 4mm) and this is probably the most significant development as it places the foot in a slightly more 'toed off' or leaning forward position in the shoe.

Another big change is that Nike have widened the heel of the Alphafly. Speaking to Elliott Heath, a Nike Running Footwear Product Manager, this widening was done to "improve the overall stability of the shoe", a move to make the shoe more universally useable by a wider sweep of runners, rather than elite and fast amateurs.

The Atom-Knit upper has been re-worked to maximise on fit make structural improvements to how the upper wraps the foot and improve breathability.

Another small change that took a lot of development according to Heath is the addition of a slither of ZoomX foam that sits sandwiched between the airpod and the outer, "We also had hurdles with this new little piece of Zoom X that comes underneath the airpods and that allows for a little bit more energy return and a little bit smoother transition. That was something that we had to test many different rounds for".

Running in the Alphafly 2

Out on the run, they’re fast. There is A LOT going on when you run in these shoes, but the 8mm drop feels more forgiving over longer distances and there is no denying that the carbon plate/pod combo really does aid propulsion.

There is a tipping point with these shoes where the benefits are negligible at slower paces and then become wholly apparent as you speed up; if you plod along they feel somewhat cumbersome and even noisy, but whenever your relevant speed picks up, the shoe gets to work and all the component parts come together to deliver that heralded increase in pace.

Fit wise, the shoe is true to size and comfortable, but comfortable like a racing seat in a Formula 1 car is probably comfortable; they're designed with a purpose and it's not a leisurely bimble about.

The footbed is quite contoured and felt a little narrow in the instep. There is also quite an abrupt transition down into the footbed under the ball of the foot, but these are only noticeable when stood about and not on the move and didn’t cause any major issues or rubbing, but worth noting if you have wider feet.

If you’re chasing PBs at the pinnacle of your running fitness, then yes, these are probably for you, but if you’re after something to help you get around 26.2 miles with some added propulsion that leaves you change for an ice cream at the end, maybe not.