The running shoe industry is awash with sustainable messaging, net-zero targets and innovative material developments that seek to assure us our running footsteps are treading lighter on the planet, but the uncomfortable truth is these incremental changes in manufacturing are only scratching the surface. And if the current unsustainable manufacturing practices and consumption patterns continue, the planet will face irreversible ecological consequences, warn scientists.

A panel of industrial engineers from Loughborough University’s Centre for Sustainable Manufacturing and Recycling Technologies (SMART) has warned that the current initiatives, investments and regulations to mitigate the impact of manufacturing on climate change are, at best, slowing down the rate of growth rather than eliminating or reversing the damage caused.

Scientists agree that to have any hope of limiting global warming to a maximum increase of 2%, greenhouse gas (ghg) emissions need to be reduced by 80% by 2050. Yet the current targets fall far short of this level. The latest estimate is that by 2050, ghg emissions will have increased by over 50%, even with all the current policies and targets in place.

‘It is the grossest kind of simplification and understatement to say we are not taking enough meaningful action,’ warns Shahin Rahimifard, professor of sustainable engineering at SMART. And the global trainer industry is a huge part of the problem – if it were a country, it would be the world’s 17th largest polluter, emitting as much CO2 as the whole of the UK.

What is sustainability, anyway?

Let’s go back to basics and ask if we’re all even speaking the same language when it comes to what we’re trying to achieve. Specific definitions of what sustainability is and how it can be achieved are difficult to agree on, but the term broadly relates to surviving on earth for a long time by protecting the environment.

Professor Rahimifard argues the term is becoming ineffectual, however, because it often refers to the ‘least worse option’ and the ‘less bad solution’ but does not go far enough towards solving the earth’s manufacturing and consumption problems. And as companies set their own emission goals, they all interpret environmental language differently.

Recognising the vagueness of the term, the London College of Fashion and publisher Condé Nast have developed a sustainable-fashion glossary. The term ‘carbon neutral’, is defined as equivalent to ‘net zero’ and, in the long term, is achieved by transitioning to an economy that doesn’t rely on burning fossil fuels. This means durable footwear that is manufactured using renewable energy and is made from regenerative organic materials. The materials and products must be transported using packaging and freight that does not rely on fossil fuels.

Which running shoes are eco-friendly?

No major brand has managed to achieve this yet, though Allbirds is perhaps the closest of the bigger players. Starting with a clean slate (it was set up in 2016), the company has been able to explicitly set its mission statement as ‘reversing climate change through better business’.

‘It’s not just about doing less and less of a bad thing; it’s about ultimately using regenerative technologies and ways to actually remove carbon over time through a more modern business model,’ says Jad Finck, Allbirds’ vice president of innovation and sustainability. ‘One of the biggest challenges of the existing incumbents is the burden of an old dirty portfolio.’

Allbirds does not calculate carbon offsetting in its race to carbon zero, but many companies do and their methods are not always transparent. In reality, many brands are reaching a self-imposed net zero target largely by carbon offsetting.

This includes schemes such as planting trees and capturing CO2, which, in itself, requires energy. Carbon offsetting has been heavily criticised for not delivering enough of a reduction in carbon and continuing the status quo, allowing the industry to avoid making radical changes to manufacturing processes. Professor Rahimifard describes a large proportion of carbon offsetting as a ‘totally shambolic’ approach that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

‘Carbon neutral doesn’t stop creating carbon, which is what’s needed,’ he says. ‘It’s an estimated type of approach. Net zero, carbon neutral, sustainability – these terms are becoming part of a dated view that doesn’t address the challenges we’re facing.’

Replacing this language are terms such as climate positive, net-negative emissions and net positive. ‘The only way is the net positive approach, because sustainability itself is not enough,’ says Professor Rahimifard. ‘Net positive is a restorative, regenerative, healing approach towards our ecosystem and production industry that puts back more into society and the environment than is taken out.’

What are the current challenges in the footwear industry?

The reality of achieving this in the world of running shoes is extremely complex, with convoluted supply chains, dozens of shoe components (65 distinct parts on average) and global distribution of products. The average pair of running shoes generates 14kg of carbon emissions during its life cycle, from raw material to landfill, with manufacturing the largest emitter in the process (9.5kg).

Then there is the release of toxic chemicals when shoes are disposed of. ‘Polyurethane and polyester are responsible for the majority of the carbon footprint,’ explains Danny McLoughlin, author of a report on ‘eco sneakers’ by running website RunRepeat. ‘Nylon also has a disproportionate impact. They have a large impact on the carbon footprint because of the amount of energy required to process the materials.’

Critics argue that the footwear industry has been slow to address its role in the climate crisis, using sustainability as a marketing ploy rather than a means to effect meaningful change. But others believe things are beginning to shift in the right direction.

‘I’m sure there will be examples of brands doing it more as a kind of marketing tool, but I think that is less common today,’ says Naomi Braithwaite, senior lecturer in fashion marketing and branding at Nottingham Trent University. ‘The way the world is moving, business at all levels is recognising we have to do something differently. So brands really want to make that change, but it’s very hard to be 100% sustainable and I think it takes time,’ says Dr Braithwaite.

If we decide to become eco-conscious consumers, it can be difficult to distinguish between greenwashing and genuine net-positive business models when it comes to choosing our running shoes. Allbirds hopes the industry will follow its example by labelling all shoes with a carbon life-cycle emission stamp, which clearly indicates output from cradle to grave. But until this happens, consumers are left to weigh up the pros and cons of the growing array of ‘sustainable’ footwear products on the market.

What can we do to shop more sustainably?

One of the simplest ways to reduce your footprint is to buy a shoe that lasts a long time and can be repaired, or recycled when it no longer performs. But recycling via charity shops and clothing banks is hugely problematic. Only 10% to 30% of donated items are actually sold in the charity shops we donate them to, with the rest sold to textile merchants, who ship much of what they buy overseas, often to developing countries. This has led to a surplus in those countries and, ultimately, huge numbers of donations being discarded.

Every week, Kantamanto Market in Ghana – the largest secondhand clothing market in West Africa – receives 15 million items of used clothing. With 40% of those products being discarded, Ghana’s capital, Accra, is overflowing with clothing waste. This waste is either burned on street corners or on huge bonfires or sent to landfills, where the overflow washes downstream into the ocean, polluting beaches and entire ecosystems as a result.

So which running brands are taking sustainability seriously?

Fortunately, some brands are now stepping in to directly recycle their products, grinding down materials to reuse in the manufacture of new shoes. In summer 2022, Merrell launched its ReTread exchange programme, which aims to keep footwear out of landfill.

The scheme involves taking back hundreds of thousands of pairs of shoes in the UK, Spain, France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Sweden and Finland. These shoes are repaired and refurbished for resale at 50% of the original price, broken down for use in new products or recycled for other uses. As an incentive, when runners send their no-longer-wanted shoes back, they receive £20 off new Merrell footwear on purchases over £80.

Going a step further, Swiss brand On has launched an innovative recycling subscription service, Cyclon. For £25 a month, members can get a fresh pair of shoes every six months, sending their old, used ones back to be ground down and recycled into new components.

Meanwhile, sportsshoes.com has partnered with running recycling initiative JogOn and delivery firm Evri to enable runners to return old or unwanted shoes, which are then distributed to charities around the world.

But critics such as Professor Rahimifard argue that while returning and reusing individual pairs of shoes may provide short-term benefits, these need to be carefully assessed against the carbon involved in shipping and cleaning the footwear.

Michael Doughty, co-founder of eco-shoe brand Hylo Athletics, says the industry is largely ‘propagating the same problem, which is a reliance on a finite resource’.

‘Currently, the sportswear and footwear market is very reliant on fossil fuel-derived materials such as polyester and nylon,’ says Doughty. ‘A lot of the sustainability work is focused on recycled content of those same materials.’

The issue raised by Professor Rahimifard, Doughty and others is that while recycling may delay products from reaching landfill and have lower carbon emissions than manufacturing shoes from virgin materials, it does not address the underlying issue and is not enough to prevent irreversible changes to the climate. Nor does it do enough to address the huge problem of overconsumption, with schemes such as Cyclon encouraging consumers to get value for money by replacing their footwear every six months.

This leads to the hugely damaging belief that shoes have to be replaced after around 500 miles, which drives overconsumption and the carbon emissions needed to satisfy demand.

What is the life span of running shoes?

Dan Lawson, ultrarunner and co-founder of upcycling outfit ReRun Clothing, says to ignore advice on when to change your trainers. ‘Shoes can last thousands of miles,’ says Lawson. ‘It baffles me how shoe companies bang on about shoes’ short lifespans; they should be doing everything to make them last longer.’ Record-breaking ultrarunner Jasmin Paris, a co-founder of The GreenRunners, agrees, estimating that she wears her running shoes for around 2,000 miles.

Addressing the issue of shoes’ lifespan, one of Allbirds’ key commitments is to double the life of its shoes by 2025 through improved construction techniques. It also highlights its machine-washable footwear’s versatility as well as its durability, because, obviously, the more situations a shoe can be worn in, the fewer shoes you need. ‘We wanted shoes that could blur categories and could be used for running, but that you could also wear for business casual, or to a restaurant,’ explains Finck. ‘We’re going after modern, timeless classics that stay in our line for a very long time.’

Newcomers Zen Running Club and Hylo Athletics follow the same mantra, stressing that their plant-powered footwear is built for durability. ‘We’re very insistent on this shoe lasting as long as any other running shoe on the market,’ says Dominic Sinnott, designer and co-founder of Zen. Meanwhile, Hylo has an NFC (near field communication) tag that, when scanned, links its customers to hyloop, a technology platform that advises on care, repair and recycling options. ‘We’re trying to encourage longer use of products,’ says Doughty. ‘The most significant decision you can make is not to buy anything new so we’re trying to encourage that through technology.’

Durability is definitely on the radar of ultrarunning superstar Kilian Jornet, who recently launched NNormaltrail shoes with Spanish footwear brand Camper. Its aim is to produce fewer, more durable products that eschew seasonal changes and fashion trends. The shoes are minimal by design, to reduce the number of seams that degrade over time and use as few components as possible.

‘I think we need to change the way we sell and buy products,’ says Jornet, ‘not to try to sell new products to replace old ones that are still in great shape but can “feel old”. That seems simple, but it involves big changes in the industry. We also need to realise that products are something we should take care of, repair and, eventually, when we need to replace them, ensure a circularity to build new products.’

Which running brands are eco-friendly?

Some brands are focusing their attention on recycled materials as a means to reach net zero (but not net positive). Merrell’s Moab Speed trail shoes are made with 100% recycled mesh lining and laces, while Nike’s sustainable materials range feature models such as Pegasus TurboNext Nature, made from 50% recycled content by weight.

Using recycled materials is, of course, a positive step, but some argue it doesn’t go far enough. ‘Those types of materials are really working with the system that we have right now, which is, unfortunately, a large amount of consumer waste is being put into the environment, such as drinks bottles and fishing nets, and these types of things are being turned into those recycled products,’ says Matt Williams, co-founder of Greenspark, which supports businesses’ sustainability goals.

But while recycled polyester uses up to 84% less energy to produce than virgin polyester, the material needs to be processed in the first place. Adidas uses waste plastic salvaged from the ocean in the uppers of its Parley shoes, which is undeniably a good thing, but these materials still require energy to be turned into the Primeknit that wraps around your feet. Nike uses polyester made from plastic bottles diverted from landfill, which, again is beneficial, but not without energy costs.

A 2021 report by RunRepeat concluded that without updating manufacturing processes, major companies were not going to make meaningful strides in reducing carbon emissions regardless of what material shoes were made from.

‘Eco-shoes are not going to save the planet – all they’ll do is kill it a little more slowly than conventional shoes,’ says McLoughlin. His report concluded that ‘eco-sneakers’ (footwear containing some recycled materials) cut emissions by less than 10% and a shoe with 100% recycled materials makes a saving of just 24%. This was largely due to the manufacturing process making up 64% of all carbon emissions, irrespective of the materials used.

You also need to be aware of just how much recycled material is being used, as recycled components may just make up a fraction of a shoe. ‘There’s definitely been a lot of greenwashing in the market, brands jumping on the green bandwagon,’ says Williams.

‘That has made it more difficult for consumers to make the right choice. How much is actually recycled? Is it 100% recycled or just 20%, with 80% still being made from virgin materials?’

Is Nike really eco-friendly?

Meanwhile, huge brands such as Nike have been promoting their ‘journey towards a zero carbon and zero waste future’ by announcing partnerships with carbon-offsetting asset management companies such as EFM). But while Nike aims to power owned and operated facilities with 100% renewable energy by as soon as 2025, there is still a reliance on recycled materials.

If the footwear industry is serious about having a carbon neutral (without offsetting) or positive impact on the planet, then renewable energy, green transportation and recycled materials are still not enough. Using renewable – rather than recycled – materials is the only way to create a completely closed-loop economy. Innovation with plant-based materials, as well as climate-positive wool, are starting to emerge. The question is whether change will occur quickly enough to prevent irreparable damage to the earth.

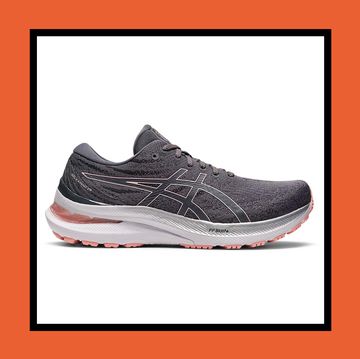

What about Asics?

In 2022, Asics launched the Gel-Lyte III CM shoe, with a carbon emission stamp of 1.95kg across its life cycle. This is significantly less than a traditional pair of running shoes, which emit 14kg CO2, according to researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The Gel-Lyte III CM contains bio-based polymers in the midsole and sockliner that are partially derived from sugar cane, but a large part of the shoe is derived from recycled polyester. Still, like other initiatives, Williams acknowledges that this is a ‘step in the right direction’ and Asics sustainability manager Minako Yoshikawa says it ‘is only the beginning’.

Could Allbirds be the most sustainable running brand?

Allbirds, which has ambitions to be emissions-free well before 2050, also acknowledges it has a long way to go. But by working with brands such as Adidas on the 2.94kg CO2e [CO2 and other greenhouse gases] Futurecraft shoe, it is trying to lead innovation. Using natural renewable materials such as sugar cane, eucalyptus, plant rubber and merino wool, the company is on target to reduce the use and carbon footprint of raw materials by 25% by the end of 2025. But its goal of ‘75% sustainably sourced materials’ still relies on both natural and recycled components – for now. ‘We think natural bio-based is the long-term vision,’ says Finck. ‘Renewable source, low carbon and, ultimately, regenerative.’

What are the most ethical running shoe brands?

Exploring material science is also key to Hylo’s vision of the future of running-shoe production. The company currently uses organic cotton, corn, algae and natural rubber to create a shoe with 60% bio content. ‘We’re not fully at that north star, but when we look to develop new shoes, we not only think about how can we improve the performance, but also how can we improve that number to 100,’ says Doughty.

Similarly, Zen Running Club is innovating with castor beans, eucalyptus, natural rubber and sugar cane while still placing an emphasis on performance. It’s an ongoing process but the company is making consistent progress. ‘We’re now getting close to 60% sugar cane within the shoe, when a few years ago it was 30%,’ says Sinnott.

So how about ‘super shoes’, which rely heavily on chemicals to create their energy-returning midsoles? Biotechnology is closing in. ‘There’s a lot of work going into it from our side to try to create a nitrogen-infused bio-based mix,’ says Andy Farnworth, Zen co-founder. ‘But the super shoe carbon-plated, eco rocker shoes aren’t there yet,’ he admits.

While the shift to renewable materials could be a giant stride towards shoe sustainability, Professor Rahimifard points out that organic materials emit methane when they degrade. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, so the end-of-life assessment has to include this. Part of Allbirds’ solution is to use carbon-absorbing wool through regenerative farming techniques in New Zealand, which means the process of producing the wool absorbs more carbon than it emits.

Positive change is happening at varying rates across the shoe industry, but when we turn the focus to ourselves as individuals, the biggest thing we can do is simply consume less. Continuing as we are is not a viable option. Professor Rahimifard cites studies that show if everyone in the world consumed at the rate of the average US resident, the resources of five earths would be needed to sustain consumption.

The required shift in mindset is not all down to us as individuals. ‘Perhaps the most important action by all manufacturers, including footwear producers, is to identify how they can create economic growth but not through producing a large volume of products and encouraging increased consumption,’ concludes Professor Rahimifard. But we can play an important part. ‘Consumers have to change as well,’ says Braithwaite. ‘It really requires a shift in consumer attitudes and consumer behaviour.’

If you want to take a step towards protecting the planet, looking for more sustainable footwear when you need new shoes can help – reducing your carbon emissions by around 9% according to RunRepeat. But ‘the most effective thing a consumer can do is buy one less pair of shoes per year, cutting their carbon footprint by a third,’ says McLoughlin.